It turns out that the leaders of Britain’s Conservative and Labour parties agree on quite a lot. The latter, Sir Keir Starmer, gave a quite a weighty speech to the Confederation of British Industry this week – which did much to help his gravitas as prime-minister-in-waiting. What has drawn most attention is his opposition to excessive immigration (not clearly defined, of course) and commitment to making Britain a high-wage, high-productivity economy. This was one of the main planks of Tory policy in at least the last two general elections, and still is – in contrast to integration with the European Union’s labour and product markets. Many in the CBI want a more flexible approach to immigration (to say nothing of more integration with the EU) – but they weren’t getting it from either leader.

The politics are obvious. Immigration is a touchstone issue in Britain, as it is in much of the world. The public thinks that the ruling elite were too relaxed about immigration and this was one of the main factors behind the populist backlash of the last decade, and the Brexit referendum result in particular. Labour are less trusted by the public on the issue, and so need to show a visibly firm line, or they won’t win back the voters that have deserted them since their last election victory in 2005. And the idea that choking off cheap labour from abroad will raise living standards is superficially plausible. In fact it was one of the more plausible claims made by the supporters of Brexit. And having done Brexit, I can understand how mainstream politicians feel the need to try and make the idea work.

But how does political necessity fare against reality? Most people seem to have very little idea of how the high-wage economy is actually supposed to work. It’s a bit like the “Australian-style points system” to manage immigration, which most people think is a jolly good idea, without having much clue about what it actually is, and how it compares to alternatives. The main target audience for economic policy ideas seems to be property-owning retired folk in the English North and Midlands (and in the English South and Wales, to be fair), who have little direct stake in a modern, functioning economy – which is all somebody else’s problem. Meanwhile they insist that there is “no room” for more immigrants – and fear that it erodes English national culture. There is therefore no particular need to explain the actual impacts of policy.

The overall economic theory is clear. If we can raise economic productivity, there is more money per head to go round to support higher wages. By choking off the supply of cheap labour from abroad, employers will be forced to use the available resources, i.e. local workers, more productively. There are two basic problems with this line of argument. The first is that higher income per head on average does not guarantee higher income for everybody. An imbalance of power in the labour market leads to high pay for the powerful at the expense of the powerless. The hope is that cutting immigration strengthens the bargaining power of less powerful. Academics argue about whether it is true – but it is not hard to find anecdotal evidence of just this. A shortage of lorry drivers following Brexit has recently driven up their pay – and with it incomes workers in related fields, like refuse collection. Still, we shouldn’t forget, as Tories sometimes do, that better wages depend on the bargaining power of workers.The second problem is that productivity is only part of the equation – the proportion of working people, or working hours per head of the total population, is critical too. In fact in a modern developed economy it is probably more important – and it has been falling due to demographic pressures, the propensity of older workers to retire on their savings, and (perhaps) lack of access to health care for longer term and mental conditions. Immigration raises the ratio of working people in the short and medium term – which is why so many people think it is a good idea.

Still, let’s put these problems aside, and try to imagine what a high-wage society looks like. It is in fact not too hard to find such societies. They are usually located in spots in the developed world with a low population density. These are often tourist hotspots and it is mainly as a tourist that I have visited them: in Australia, New Zealand, Western Canada, Norway and Switzerland. The first thing you notice is that there aren’t many workers. If you are on safari in Africa, you will get a tour guide and driver as a minimum. In Canada and Australia the same individual does both roles. Go into a shop and there are few people to serve you. And there aren’t many shops. At hotels you carry your own bags. You get something of the Tesco automated checkout phenomenon. Self-service amounts to higher productivity for Tesco, but all they are doing is making you do more work for yourself. An experienced cashier is much quicker. In a high-wage economy you may find yourself eating at home instead of at restaurants – or inviting friends for drinks at home rather than trying to find a bar. The cost of services involving human contact is relatively higher.

So where are the workers? Not so many in the tourist spots, though there will be people delivering high-end products or services at quite a cost. They are mostly somewhere else, delivering highly productive goods or services. In Australia and Canada there is mining; in Norway there is oil; in Switzerland there is sophisticated manufacturing (chemicals and such) and banking. These are linked to exports, so that high-wage countries tend to be high-exporting ones, usually running trade surpluses.

Here’s the key. Some gains to wages for the less well off can be made by reducing profits and cutting top-level pay. But not enough and not sustainably. A large proportion of workers need to be employed in highly productive fields. If businesses simply raised prices to pay for higher wages, we end up where we started by putting so many things out of the reach of less well-off workers. But high productivity industries in the modern era are very productive indeed. They don’t employ many workers and usually need exports to to be sustainable.

And so we can start to see the characteristics of a high-wage economy. Workers must have strong market bargaining power, generally by being in short supply. There must be a strong, highly productive core to the economy, generating a substantial export trade (overall trade doesn’t need to be in surplus in theory – though in practice this often seems to be the case). And most people will have to put up with doing more things for themselves, as the price of services is high – and especially in rural areas. Taxes are also likely to be quite high to to support public services such as health and education – as a strong state underpinning of these, and an effective social safety net, is all part of the ethos – and supports the strong bargaining position of workers generally.

In Britain the problem is obvious. Labour shortages are improving the bargaining position of workers. We are moving towards a self-service economy as these labour shortages sweep through the hospitality industry amongst others. But what of the highly productive core? Here we are faced with a fleet of ships that have sailed. Fossil fuels are depleted and anyway a problem in the zero-carbon future. The country’s manufacturing has been hollowed out – the trade deficit is of very long standing. Financial services provided a lot of punch in the earlier years of the 21st century, but are going through rough patch in the 2020s. Brexit is widely blamed, but in truth the problems are wider. A lot of the strength of the mid-noughties turned out to be fictional – and it was very centred on London. The country needs to look to the future, and not try to recreate old glories. Here the parties do differ a bit. There doesn’t seem to be a coherent Conservative strategy at all. Their basic idea is to create fruitful conditions for investment and sit back and wait. Liz Truss, Mr Sunak’s predecessor, did lend some coherence to this approach. She wanted to create a low-tax, low-regulation haven for footloose international businesses. This idea quickly collapsed, leaving Mr Sunak plying platitudes about innovation. His government looks increasingly paralysed by internal divisions and unable to implement any decisive strategy.

Labour’s big idea is the green economy (something promoted by the Lib Dems and Greens too). This entails a massive investment programme designed to transform the country’s infrastructure as well as develop export industries. This is a good idea, but a lot of the work involved (home insulation for example) is not high-productivity. And there is intense competition for the rest – batteries and wind turbines for example. Still, it doesn’t do to underestimate British inventiveness, and public-private partnerships in this area surely provide part of the answer. Also renewable energy does offer high productivity, without the need for exports. There are other ideas. I have often talked about health care and related services, where Britain has a promising base – and where the NHS offers world-class data for developing new treatments – as the covid episode showed.

But there is a gorilla in the room that the politicians don’t want to talk about. This isn’t Brexit (though they don’t want to talk about that either). This has created problems for developing export industries – but other EU members are further down the path of developing exports and British industries struggled to compete with them in the single market. Britain’s trading problems got worse within the EU, after all, even if there were compensations. The gorilla is public sector pay – especially if we include the issue of social care. High wages mean high levels of pay in the public sector. Not all public sector jobs are badly paid, but the pressure of a tight labour market is putting public services sector under pressure. Staffing shortages are rife in many parts of it. Meanwhile part of the government’s anti-inflation strategy is to hold back public sector real pay levels – which is making matters worse. The answer is either to shrink the public sector or to raise taxes. Of course the politicians hope that an explosion of high-productivity private sector jobs (with associated tax revenue) will come to their rescue. But it won’t happen in time, if it ever does.

This is a tough place to be in, so it’s no surprise that our politicians are slow to confront the truth of it. I have to admit that it is forcing me to rethink some of my assumptions. But I do think that the vision of a high-wage economy is worth pursuing. The main alternative being offered by those interested in social equity is a universal basic income paid by the state. I am deeply uncomfortable with that idea for a number of reasons. Given that, here are two things to be thinking about.

The first doesn’t involve any great rethinking on my part, but remains politically toxic. We need higher taxes. This is not just on various soft-spots and loop-holes in the wealthier parts of the economy – schemes that are predestined to disappoint. Higher taxes need to affect most people. This is because public spending will have to rise to accommodate higher public sector pay – and we need to manage down the level of demand in the rest of the economy to help stabilise it, to say nothing of limiting the need to borrow money on world markets. Of course public sector productivity can be improved (though I prefer the word “effectiveness” to “productivity” – as a lot of the solution is lowering demand by forestalling problems), reducing the need for spending. But our political class, our civil servants, and the commentators and think tankers that critique them, have almost no idea how to achieve this. They are stuck in an over-centralised, departmental mindset. What is needed is locally led, locally accountable, cross-functional, and client-centred services – an idea that is so alien to British political culture that most people can’t even imagine it. So we can’t count on that idea and must settle for replacing the dysfunctional with the merely mediocre, with no cost-saving.

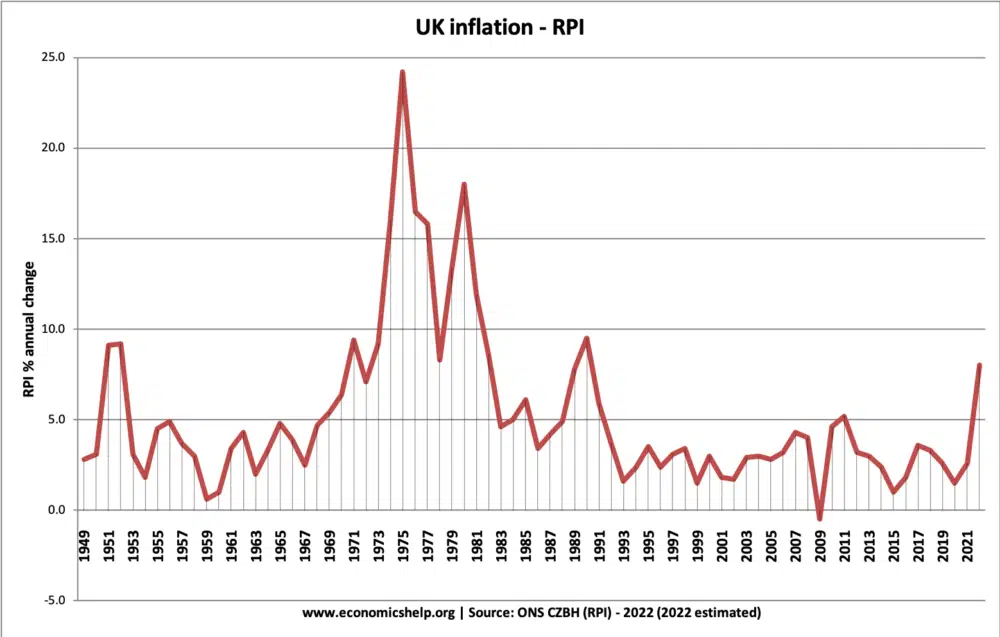

The second idea is even more contentious, and I haven’t properly thought it through yet. It is that inflation is an essential part of the process of readjustment, and we have to tolerate it to a degree – provided that the source of that inflation is a rise in pay for the less well-off. As somebody who grew up in the 1970s, I hate inflation. I think it undermines trust between the state and the governed. I have never subscribed to the view of liberal economists that it can be a tool of economic management. But there have to be exceptions. One example was Ireland in the 2000s, as that country worked through its economic transformation as it integrated with the EU economy, which did involve a spurt in productivity. Wages rocketed, driving inflation up. Ireland was in the Euro, so there was no ability for the currency to appreciate to ameliorate the effect. This was the only way for the country to reach the sunlit uplands – which didn’t stop the European Central Bank from criticising it – something my economics lecturer at UCL said was absurd.

Britain’s position is different from Ireland’s. We haven’t had that productivity spurt. There is nothing to drive an appreciation of the currency. But we want wages amongst the less well-off to rise. Price rises are part of the adjustment – with inflation acting as a tax on the wealthy, as part of a redistribution process. Meanwhile we need to drive capital investment – most renewable energy is very capital intensive, for example – as are most of the ideas for developing higher productivity. That means keeping interest rates low. Which won’t happen if interest rates are jacked up to combat inflation. And, as suggested already, to the extent that inflation needs to be managed, higher taxes are a better way to do it.

This is quite a progression in my personal thinking (and thank you to regular commenter Peter Martin for helping me along the way – though doubtless we still disagree). But trying to get to the fairer, more sustainable society we seek is going to require many of us to change our thinking – and put up with some things we don’t like.