“A Britain that works for everyone.” This is what Britain’s Conservatives say they want to achieve under the new prime minister, Theresa May. Partly, of course, this talk is meant as an attempt to divert attention from the difficult choices implied by Brexit. But there is an issue that is slowly coming to dominate the life-chances of “everyone”, and could be even more important than Brexit: housing. Or to give this a bit more precision: the high cost of buying or renting residential property. In order to fulfil their slogan, the Tories will have to make progress on this. Will they?

What brought this home to me last week was a report that people born in the 1990s (the so-called millennials) are worse off than those born in the 1980s at the same time in their lives. This is startling for a society that has, generally speaking, benefited from economic growth over the last 30 years, and where educational standards are rising. And the reason is easy to see: compared to people born even ten years earlier, many fewer millennials can afford to buy their own homes. They are unable to benefit from a general rise in property prices that has proceeded apace over that 30 years. Meanwhile rental costs have gone up too, which only makes the gap wider. This phenomenon does not just apply to Britain’s overheated southeast – it afflicts most major urban centres, to say nothing of popular university cities like Oxford and Cambridge.

Why is this such a big issue? The millennials themselves are not particularly important electorally, especially as so many of them show little interest in the political process. But their troubles worry their parents. And the trend is evident from before the millennial generation. More importantly, the generations following the millennials will be equally deprived. The numbers of property have-nots are growing, and property wealth is being concentrated into a smaller number of hands. High rents is a cause of hardship for ever increasing numbers of people – and a cause of rising homelessness, with all the other problems that brings in its wake.

Politicians are increasingly aware of this. Conservative leaders are talking the talk. Mrs May has appointed a new cabinet level minister of housing, Sajid Javid, who talks of a moral crisis. All leading politicians talk grandly of building many more houses. But there are two political problems, which are linked. The first is that the crisis arises from a profound failure of market incentives. And the second is that any policy that actually works is going to hurt a lot of politically influential people. This combination presents a test for Mrs May that she is unlikely to pass. It is one of the few decent opening in British politics for the left.

First consider market forces. Read The Economist and you might think that the housing problem is quite simple at heart. It is a failure of supply to meet the increased demand for housing from a rising population and changes to lifestyle that mean more people want to live alone. And there is a ready culprit for this: restrictive planning laws and NIMBYs who resist new housing developments, which between them surround our cities with over-protected green belts. This glib explanation contains some truth, but it misses two awkward points: much land where development is permitted is not being developed because owners would rather wait – “land banking”; and loose monetary policy has pushed up the cost of housing regardless of supply and demand.

Consider the first point. Property developers profit massively from increasing property prices. Indeed, it is central to their business model. They like to build cheap houses to maximise their profits from land trading, fighting furiously any regulations that might make homes more thermally efficient, for example. It is not in their interests to increase supply to levels where the value of property starts to come down. For all their moaning, they are quite happy with the situation as it is – though they would love to get their hands on green belt land with permission to build, and bank that too. A similar logic applies to rental values, since so many new properties are bought to let. The economic incentives do not point to the private sector solving this problem by themselves. In fact many private sector actors are likely to oppose any policy that actually bites, since that means cutting rental and sale values.

The effects of monetary policy are less understood: by this I mean the way governments and their central bankers have had no real qualms about rising levels of debt used to finance private house purchases. This has been happening since monetary policy was let off the leash by the collapse of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates in 1970. The extra monetary demand for housing set off by this increased availability of finance has not been matched by an increased supply of housing. Indeed it is about this time housebuilding slowed down. Easy money has simply led to the inflation of land prices.

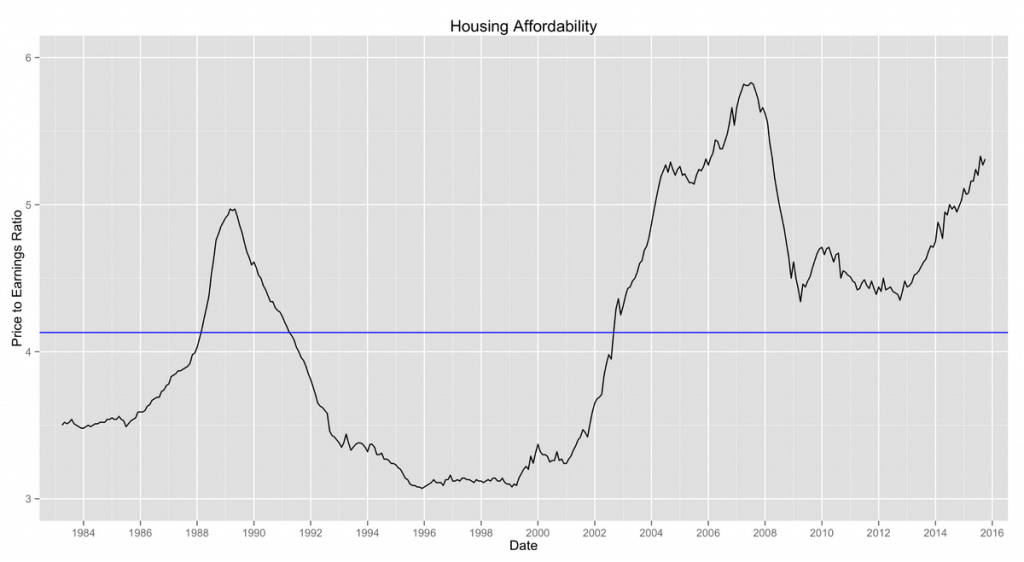

To illustrate this, look at this graph of the ratio of house prices to earnings from Wikipedia (By D Wells – Own work):

We should expect to see house prices rising in line with earnings, given its relatively limited supply. We can see that the ratio of prices is tied closely to monetary conditions. Monetary conditions were loose in the late 1980s (the Lawson boom), but had to be tightened as inflation started to get out of hand. That caused a crash that is seared into the memory of older Tory politicians – the years of negative equity. Then things eased, with the mid to late 1990s and early 2000s being years of easy money. The financial crash of 2008 tightened things up, but now conditions are loose again.

Of course easy money and land-banking are self-reinforcing. If property prices dip, property developers can be confident that monetary conditions will ease and come to their rescue.

If I am right about these two problems lying behind Britain’s housing crisis, the solution is quite easy to see. First there needs to be a massive public-sector house building programme, including a large proportion of good-quality social housing, available at rents well below the current market level. This is best done by local and regional authorities, and financed by allowing them to borrow much more. This would put downward pressure on rents, which is perhaps the most urgent aspect of the housing crisis. It would also make it much easier to tackle homelessness.

The second thing that needs to be done is to tighten monetary policy. This may be by using some form of quantitative control on housing debt, but it may also mean raising interest rates. The main idea would be to encourage banks to finance local authority housebuilding, rather than private mortgages. This will require political courage, as it means, for a time at least, property prices falling without making property more affordable (since it will be harder to get finance) – as happened briefly after the crash of 2008/09.

The good news is that the first of these two groups of policy is fast becoming consensus on the left – sweeping in Labour, the Greens and the Liberal Democrats. And yet it will be very hard for the Conservatives to stomach. They associate social housing with left-wing voters. It may also upset NIMBYs where the estates are to be built, to say nothing of hordes of people who have invested in property to let – all natural Tories. Tory politicians talk freely of raising large sums of money to push house construction forward. But I have not heard any talk of giving a serious boost to social or public sector housing, or giving local authorities more freedom. It sounds horribly like subsidies for the private sector that will end up by inflating prices and developers’ wallets further.

On the second issue – reducing the volume of private housing finance – I see little sign from anywhere in the political spectrum of this being taken up. This is unsurprising. It would mark a profound change in economic management, which is heavily based on monetary policy. And change would cause outrage in Middle England, attached to its property values. And yet the current way speaks danger. It is increasingly dependent on ever increasing property prices, as these lose touch with incomes. It is a bubble that will surely burst at some point. Even so, I am sure that the left is closer to this policy change than the right. One implication is that more of the load of economic management will be taken by fiscal rather than monetary policy. The left is much more comfortable with that, though I suspect few have taken on that it means supporting austerity at the top of the economic cycle.

Mrs May talks much of making life better for the hard-pressed in our society. Lower rents are surely by far the best way to achieve that. Does she and her party have the stomach for it? If not, the left will have its chance.