The story goes that when Russian chief minister Grigory Potemkin took Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia, on a tour to the south of her realm, he stage managed the process by co-opting peasants and painting up the villages she passed through to give her a false impression of the prosperity of the area, and her popularity. The expression “Potemkin village” has entered the language. Russia’s assault on Ukraine, launched in February, conjures up a similar image. Much of what we see of Russian power has been set up to give the right appearance. But things don’t actually work.

This was evident from the first days of the war. We were told, and Western experts accepted, that Russia had a modern army capable of quickly overwhelming Ukraine’s ramshackle affair. But Russian troops had not been properly trained; their equipment was not up to standard; their logistics systems could not cope with more than minor movements of troops. The army could produce glitzy videos of troops in action, but it was not up to the real thing.

We are now witnessing another example. Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, has ordered a partial mobilisation, to provide 300,000 extra troops to complete the campaign. He set out some clear principles for this action: the recruits would have military experience and would be given extra training, certain professions would be protected, and so on. These followed clear Russian laws about who was eligible and how they should be treated. All this has been ignored by the officials trying to implement the orders, who simply focus on providing enough bodies in any way they can, and dispatching them straight to the front without training. The Russian state is incapable of following instructions properly – the systems needed to do so aren’t there. At at the front, Russia’s army is being hollowed out and filled by untrained and unmotivated recruits – even supposedly elite units. Meanwhile the impact of the mobilisation on Russia’s productive workforce has been doubled by people fleeing in fear of being drafted – unable to accept assurances that they aren’t at risk.

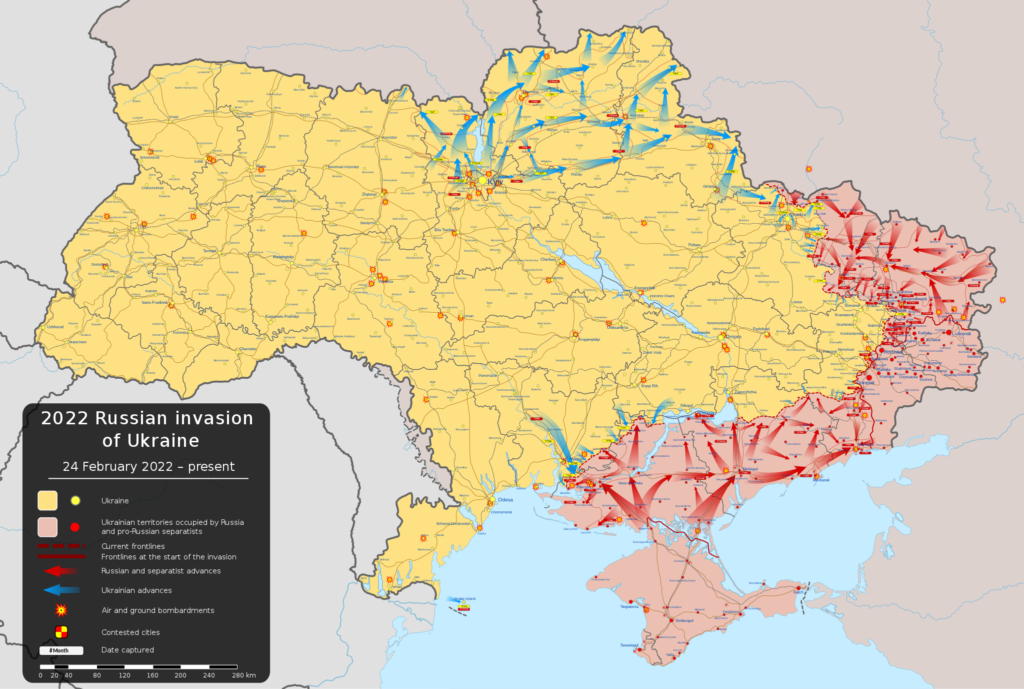

I last commented on the war towards the end of August. At the time there seemed to be a bit of a stalemate. Russian attacks in the east had run out of steam. Ukraine’s much talked-of offensive in the south looked rather underwhelming. But a couple of weeks later, the picture changed dramatically. Ukraine launched an offensive in the north-east, in Kharkiv oblast, and caught the Russians on the hop. The Russians were routed and Ukraine recovered swathes of territory. Since then Ukraine’s progress has slowed there, but it continues. They recaptured the significant town of Lyman last weekend and have made further advances since. In the south, things have been much less clear. Ukraine had been making slow but costly progress. They were using American and European supplied advanced artillery and rocket systems to degrade Russian logistics – but progress in doing so was slower than hoped – the Russians have responded with dispersal tactics that have proved quite effective. But more rapid progress has been reported in the last few days. Ukraine hopes to isolate the Russian forces around Kherson city and force their retreat or surrender, without destructive street fighting, and complete the recapture of all territory to the west of the great Dnieper river, before the expected autumn rains.

Ukraine now has two big advantages. The first is that Russian frontline troops are badly degraded. Their artillery still seems to be effective, and remains their battle-winning edge, though Ukraine’s use of Western artillery technology has redressed some of this advantage. The second advantage is that of a central position. It is much easier for Ukraine to switch resources between the various fronts than it is for Russia. Russia can’t deploy decisive concentrations of artillery everywhere, so Ukraine can attack areas where Russia is weaker. The military situation seems to be deteriorating rapidly for the Russians – and feeding untrained recruits into battle will make little difference.

The Russian leadership is now getting more desperate. The original intention was that the operation would not have a major adverse impact on the Russian public. One Russian apparently put it something like this: “It’s like de-fleaing your cat. Easy for you; painful for the cat; fatal for the flea.” The mobilisation changes all that. Now the war is serious for the public, and that has undermined the regime’s popularity. Meanwhile supporters of the war are becoming increasingly critical of the leadership, and the regime does not know how to handle this. The situation is getting harder for the regime to manage.

But does Mr Putin have an ace up his sleeve? He has invested a lot in the country’s nuclear arsenal, and he is desperate to show that this investment has clear benefits. Can he use nuclear weapons to tip the balance back? He is probably not too worried about the dire warnings coming out of the US. He has the means to respond to a direct escalation by them, by threat of more nuclear weapons. And as for sanctions, what more can the West do? And would it really lead to a loss of passive support from most of the rest of the world, including China and India? If they aren’t outraged by the trampling of Ukraine’s territorial integrity, will anything short of a direct threat worry them?

But how useful would nuclear weapons actually be? Russian forces patently aren’t equipped to deal with a contaminated battlefield. Firing weapons at Ukrainian logistics centres would destroy whatever remains of the Russian narrative of avoiding civilian deaths. And if they win, do they really want to clear the mess up? And if they don’t, what’s the point? Gradually people are steeling themselves for some form of nuclear demonstration.

That would change things in unpredictable ways. But we might pause to ask how Russia got itself into this mess. Post-communist Russia is a joint enterprise between its intelligence services and organised crime. Mr Putin seems to have had a soft spot for criminals from quite early. Doubtless the admired the way they could get things done – as well as they opportunities for personal enrichment they offered. It was a good fit with the shadowy, menacing way in which the intelligence services, his own powerbase, like to work. But this combination destroys the rule of law, and undermines institutions, including most of the armed services. It creates the Potemkin state. (In the metaphorical sense – actually the real Potemkin was an effective administrator, overseeing one of the more positive periods in his country’s history. Potemkin did not create a Potemkin state).

Meanwhile, as his failings become ever more exposed, Mr Putin gets more desperate. His most recent gesture was the annexation of four regions of Ukraine (in a ration to Crimea, already annexed), though Russia won’t say what the boundaries of the annexed states are. The desperation brings danger to the rest of the world. But it also makes compromise harder to envisage. We are moving into an even scarier phase.